Welcome To

Avian and Exotic Animal Care

+ Veterinary Hospital

Since 1996

The Vets for Unusual Pets ®

Since 1996, we have been the Triangle’s only veterinary hospital focused entirely on the care of exotic pets, including birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish, exotic mammals, and invertebrates. Our team of experienced veterinarians and staff are dedicated to providing specialized care for non-traditional pets. We work collaboratively in most cases, meaning your pet benefits from the expertise of multiple doctors. This ensures comprehensive treatment for each unique situation, giving your pet the focused care they deserve.

Specialized Care for Your Exotic Pet’s Needs

Avian and Exotic Animal Care focuses exclusively on exotic pets, providing a calm environment free from the typical stress of dog and cat clinics. We offer comprehensive medical, dental, and surgical care for a wide range of non-traditional pets, along with house calls for those who prefer in-home visits.

Mammals

Amphibians

Birds

Reptiles

Fish

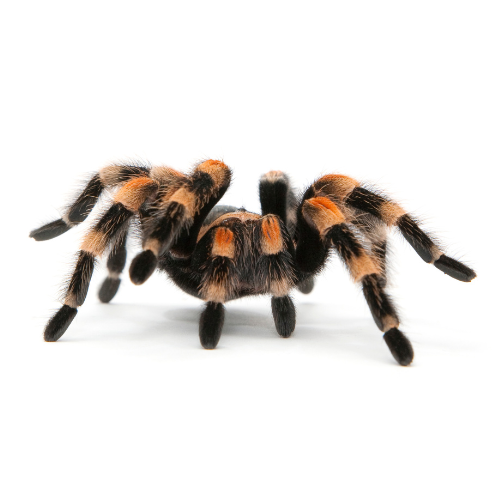

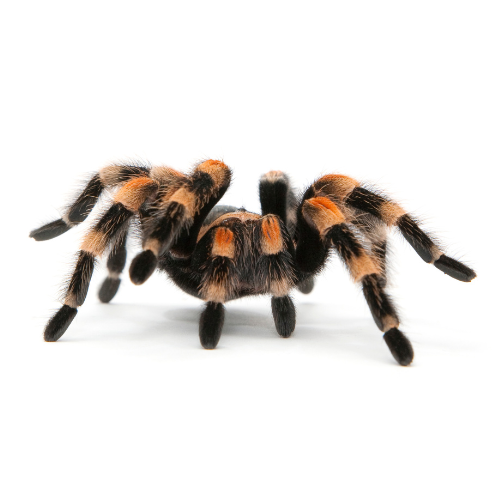

Invertebrates

Mammals

Amphibians

Birds

Reptiles

Fish

Invertebrates

why is an

Avian and Exotic Animal Veterinarian Important?

Most veterinary programs primarily focus on small mammals or large farm animals, leaving exotic pet care underrepresented. Treating birds and exotic species like traditional pets can lead to serious harm. Our veterinarians exclusively treat only these unique animals, dedicating their practice entirely to providing exceptional care. We also go above and beyond, often earning more than twice the required continuing education hours each year to stay current with the latest treatments.

Our team plays a leading role in advancing exotic animal medicine worldwide. Our doctors frequently publish research, contribute to textbooks, and lecture internationally. We even host veterinarians and students who come to learn from our expertise. When you visit Avian and Exotic Animal Care, you can trust that your exotic pet is receiving the highest level of care possible.